So as to prevent the scarf of liberty

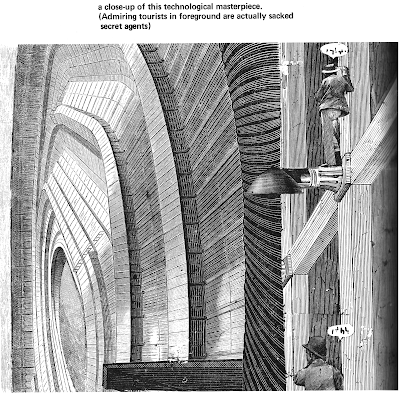

Max Ernst, La Femme 100 Têtes (1929)

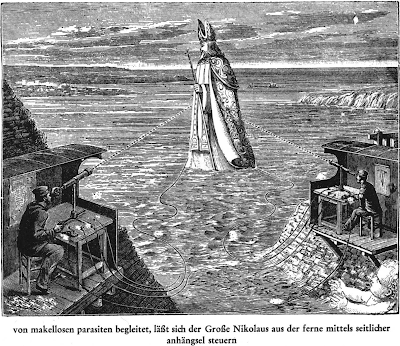

Norman Rubington, aka 'Akbar del Piombo', Moonglow (1969)

Like most modern artforms, collage was invented by Picasso in the early years of his century; but it was perhaps better suited, at least on a philosophical level, to the Surrealist vision—the sewing machine and umbrella together on the operating table, to use the old cliché, or the yoking together by violence of heterogeneous ideas, to use the still older cliché, or the mulier formosa superne, desinans in piscem, to use the oldest cliché of all. A short time after Picasso had finished glueing daily ephemera onto his canvases, Gertrude Stein began fricketing around with a collage of words in Tender Buttons, published in 1914, on the eve of the Collage to End All Collages. Thus was born, before the modernist aesthetic had a chance to breathe, the aesthetic of the postmodern—the celebration of the fragment and the fragmentary. Ultimately, Henry Miller's Black Spring, and Burroughs' Naked Lunch and The Soft Machine.

Black Spring was published by Jack Kahane's great avant-garde engine, the Obelisk Press, which also let filth by Anaïs Nin and Lawrence Durrell loose on the general public. Kahane's son, Maurice Girodias, founded an even more infamous press in 1953, the Olympia, notorious for publishing the first editions of Lolita and Naked Lunch. Its 'Travellers' Companion' series, with its distinctive forest-green covers, is a fount of surreal delights: my collection includes Paul Ableman's I Hear Voices, William Talsman's The Gaudy Image, J. Hume Parkinson's Sextet and Jett Sage's Crazy Wild Breaks Loose. In his introduction to the Olympia Reader, Girodias recalls that one of his closer cohorts was an American painter living in Paris—Norman Rubington—who translated Queneau's Zazie dans le Metro, as well as producing a riot of his own material. Girodias suggested the pen-name Akbar del Piombo for Rubington's several collage graphic-novels, including Fuzz Against Junk (1959—some illustrations here) and Moonglow (1969). (The credits for the latter in fact read, 'by OSP, ex-military computer (Orthophonic Syntax Pullulator) decoded by Akbar del Piombo with collages by Rubington.')

He took the style from an earlier series of works by Max Ernst, executed in the 20s, of which La Femme 100 Têtes was the first full example. Giornale Nuovo has two posts on the work. Like Picasso, Ernst was a restless innovator: not only did he do radical things with the collage technique, he also perfected the decalcomania of his friend Oscar Dominguez, and even preempted Pollock's drips in the mid-40s. He had been dabbling with single-image collages right from the start, but in La Femme and its more famous sequel, Une Semaine de Bonté, he ripped steel-engravings from Victorian texts and arranged them into disorienting fantasy tableaux. I own a German edition from 1962, square, white and plain, in a card slipcase.

Norman Rubington, aka 'Akbar del Piombo', Moonglow (1969)

Like most modern artforms, collage was invented by Picasso in the early years of his century; but it was perhaps better suited, at least on a philosophical level, to the Surrealist vision—the sewing machine and umbrella together on the operating table, to use the old cliché, or the yoking together by violence of heterogeneous ideas, to use the still older cliché, or the mulier formosa superne, desinans in piscem, to use the oldest cliché of all. A short time after Picasso had finished glueing daily ephemera onto his canvases, Gertrude Stein began fricketing around with a collage of words in Tender Buttons, published in 1914, on the eve of the Collage to End All Collages. Thus was born, before the modernist aesthetic had a chance to breathe, the aesthetic of the postmodern—the celebration of the fragment and the fragmentary. Ultimately, Henry Miller's Black Spring, and Burroughs' Naked Lunch and The Soft Machine.

Black Spring was published by Jack Kahane's great avant-garde engine, the Obelisk Press, which also let filth by Anaïs Nin and Lawrence Durrell loose on the general public. Kahane's son, Maurice Girodias, founded an even more infamous press in 1953, the Olympia, notorious for publishing the first editions of Lolita and Naked Lunch. Its 'Travellers' Companion' series, with its distinctive forest-green covers, is a fount of surreal delights: my collection includes Paul Ableman's I Hear Voices, William Talsman's The Gaudy Image, J. Hume Parkinson's Sextet and Jett Sage's Crazy Wild Breaks Loose. In his introduction to the Olympia Reader, Girodias recalls that one of his closer cohorts was an American painter living in Paris—Norman Rubington—who translated Queneau's Zazie dans le Metro, as well as producing a riot of his own material. Girodias suggested the pen-name Akbar del Piombo for Rubington's several collage graphic-novels, including Fuzz Against Junk (1959—some illustrations here) and Moonglow (1969). (The credits for the latter in fact read, 'by OSP, ex-military computer (Orthophonic Syntax Pullulator) decoded by Akbar del Piombo with collages by Rubington.')

He took the style from an earlier series of works by Max Ernst, executed in the 20s, of which La Femme 100 Têtes was the first full example. Giornale Nuovo has two posts on the work. Like Picasso, Ernst was a restless innovator: not only did he do radical things with the collage technique, he also perfected the decalcomania of his friend Oscar Dominguez, and even preempted Pollock's drips in the mid-40s. He had been dabbling with single-image collages right from the start, but in La Femme and its more famous sequel, Une Semaine de Bonté, he ripped steel-engravings from Victorian texts and arranged them into disorienting fantasy tableaux. I own a German edition from 1962, square, white and plain, in a card slipcase.

her fiery smile will fall down from the hillsides

as black frost and white rust

as black frost and white rust

and the butterflies begin to sing

accompanied by immaculate parasites, Santa Claus allows

himself to be controlled from afar by means of lateral appendages

himself to be controlled from afar by means of lateral appendages

the dovecote stands open to the slashed child

There is little obvious connection between the images. The hundred-headed woman of the title, really more of a cipher, is variously called Wirrwarr and Germinal. The other cipher-figure is Ernst's totem bird Loplop, in my edition called 'Der Vogelobre Hornebom'. Although the original is French, I prefer the German, its music harsher, more alien, a better fit for his images. Stuck in my mind for a long time is a bit of Germanic dada from Ernst's collage-painting The Hat Makes the Man (1920):

bedecktsamiger StapelThe thread and narrative of the sequence is in fact a series of motifs, from birds to various roundels to falling timbers to skeletons and popes. The more famous La Semaine, of which a Dover reprint is easily available, is divided into days corresponding to physical elements and visual motifs; its structure is simpler and less intuitive than La Femme, which in turn is more surprising and inventive. They correspond, in their own way, to the two automatic texts produced by Brèton and Soupault, Les Champs Magnétiques and La Conception Immaculée, the first being freeform and anarchic, the second segmented and systematised. I prefer the former in each case.

mensch nacktsamiger wasserformer

("edelformer") Kleidsame nervatur

auch

!umpressnerven!

Moonglow is a much rougher work, clearly the product of an anti-authoritarian, youthful and narcotic 1960s, an effluvium of the Beat culture. The images tend to be less beautifully arranged than those in La Femme, and are often isolated on a white page, as the first two below. There is a loose story, utterly nonsensical, set in a nuclear fallout after WW3 has sent mankind underground, about a boy named Harry Moonglow whose body begins to change without end: 'on his twentieth birthday Harry graduated with honors, starred in high school production of '100 days in Sodom' . . acting was in his blood . . But something else was in it as well . . as Harry discovered one day in the bathroom. The face staring back in the mirror was not his own. Every time a muscle twitched, a new apparition occured [sic]. He saw in quick succession, Herbert Hoover, Al Capone, Groucho Marx, Batman, etc.' He is recruited as a spy by the CIA, but by the end of the book WW4 has broken out and a flood has covered the earth.

2 comments:

Many thanks for this—I’m almost persuaded to seek out a copy of La Femme 100 Têtes for myself… The del Piombo images are interesting too: I think this is the first I’ve actually seen of any of them.

Nice blog...I just read La Femme 100 Têtes from this blog. Thanks to share.

Post a Comment