History of the Nod: Part I

When the mean rascal Kayin whacked his own brother Hevel, he was cursed by Don Jehovah to a lifetime of wandering—doh!—this occurs in Genesis 4:12:

But a different tradition had arisen even before Jerome. The Septuagint Greek translation, started around 300 BC, gives this version of 4:16:

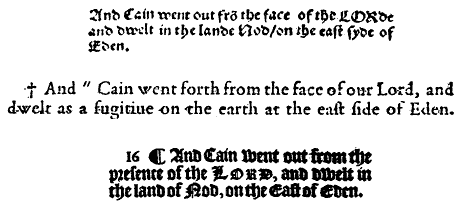

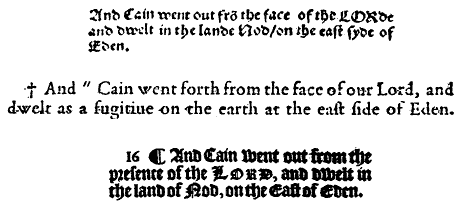

Here, the word nod is rendered as a name: the Land of Naid (or Nod). When Tyndale produced his own heretical translation of the Bible in 1525—sources differ as to which version he used—he wrote 'And Cain went out from the face of the Lorde and dwelt in the lande Nod / on the east syde of Eden.' The 1611 King James, which follows Tyndale in most details, provides the now-canonical verse: 'And Cain went out from presence of the Lord, and dwelt in the land of Nod, on the East of Eden.'

ki ta'avod et-ha'adamah lo-tosef tet-kocha lach na vanad tihyeh va'arets'When you work the ground, it will no longer give you of its strength. You will live as fugitive and wanderer on the earth.' The underlined syllable, nad, denotes wandering. Strong's Hebrew Bible dictionary gives the following list of senses for the basic root: 'to nod, i.e. waver; figuratively, to wander, flee, disappear; also (from shaking the head in sympathy), to console, deplore, or (from tossing the head in scorn) taunt:—bemoan, flee, get, mourn, make to move, take pity, remove, shake, skip for joy, be sorry, vagabond, way, wandering.' The word is echoed again in 4:16:

vayetse kayin milifney yahweh vayeshev be'erets-nod kid'mat-eden'Kayin went out from the presence of the Lord, from the east of Eden, and dwelt as a wanderer on the earth'. Here nod is a cognate of nad. (See here for a recent post on the topic by the young Jewish scholar, Simon Holloway.) Jerome (405 AD) renders 4:16 as 'Egressusque Cain a facie Domini, habitavit profugus in terra ad orientalem plagam Eden.' The 1370s Vulgate translation supervised by the heretic John Wycliffe offers 'And Caym, passid out fro the face of the Lord, dwellide fer fugitif in the erthe, at the eest plage of of Eden.' Likewise, the standard Vulgate in English, translated as Catholic propaganda by Gregory Martin in 1609 and now known as the Douai-Rheims Bible, reads 'And Cain went forth from the face of our Lord, and dwelt as a fugitiue on the earth at the east side of Eden.'

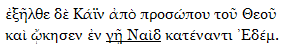

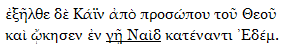

But a different tradition had arisen even before Jerome. The Septuagint Greek translation, started around 300 BC, gives this version of 4:16:

Here, the word nod is rendered as a name: the Land of Naid (or Nod). When Tyndale produced his own heretical translation of the Bible in 1525—sources differ as to which version he used—he wrote 'And Cain went out from the face of the Lorde and dwelt in the lande Nod / on the east syde of Eden.' The 1611 King James, which follows Tyndale in most details, provides the now-canonical verse: 'And Cain went out from presence of the Lord, and dwelt in the land of Nod, on the East of Eden.'

Top to bottom: Tyndale's version (Antwerp, 1530), the 1609 Douai-Rheims, and the original 1611 blackletter King James. Of note: Tyndale's text predates the 1565 division of the Bible into verses, marked with crosses in the D-R; and also the KJV's moonlet paraph-mark, an early form of the ¶.

*

*

In his Old Testament commentary, the reformer John Wesley remarked: 'in the land of Nod—That is, of shaking or trembling, because of the continual restlessness of his spirit. Those that depart from God cannot find rest any where else'. The English word 'nod' has itself a primary sense akin to 'shaking', and etymologists had already suggested a Hebrew origin for it. John Minsheu (The Guide into Tongues, 1627) provides this entry:

to Nodde, or becke, ab Hebr. Nod, i. [intransitive] nutare [nod], vagari [wander].Stephen Skinner (Etymologicon, 1678) follows Minsheu. I translate the relevant parts of his entries for Nod and Noddle:

the Noddle, or hinder part of the head, q. pars capitis nutans [nodding part of the head], à [Hebrew] Nod, i. nutare, vagari, hinc inde moueri [move to and fro].

Nod, from Latin Nutus [a nod of the head]. . . To become drowsy. The origin of the word may also be from German Neygen; see Noddle.I was disappointed to find that Robert Govett declines to make the connection in his own fantastical dictionary (1869) of English words derived from Hebrew; but thankfully he has a deliverer in Isaac Mozeson, a bright star in the Merrit Ruhlen school of linguistics. Mozeson's The Word (1995) provides an extensive entry for Hebrew NOD/ND, connecting it not only to English nod but to the Latin roots nuere, movere, and even natare (to swim). Sadly, a careful perusal of that meisterwerk of mass-comparison philology, Bomhard and Kerns' The Nostratic Macrofamily (1994), yielded no results.

Noddle, Head, following Minsheu q. d. The nodding part of the head, from Hebrew Nod, to nod the head; see Nod.

The word's true affiliations and sense-development will be expounded in the second part of this history.

1 comment:

A thorough and informative post: thanks for the hat tip.

Post a Comment