Ekphrasis and memory

In this post I return to my recent critique of ekphrasis with a more sophisticated historical and theoretical context. Supposedly. It's longer, anyway.

An attack on ekphrasis is one of the central themes of G. E. Lessing's Laocoon (1766), a circumambulatory and much-celebrated essay on the arts, marking something of an anticipatory watershed between the neoclassic and romantic eras of German taste. Lessing's core argument was that painting and poetry are not equivalent art-forms—a view he ascribes to several of his contemporaries—because the first deals with things side-by-side in space, and the second deals with things one after the other in time.

An attack on ekphrasis is one of the central themes of G. E. Lessing's Laocoon (1766), a circumambulatory and much-celebrated essay on the arts, marking something of an anticipatory watershed between the neoclassic and romantic eras of German taste. Lessing's core argument was that painting and poetry are not equivalent art-forms—a view he ascribes to several of his contemporaries—because the first deals with things side-by-side in space, and the second deals with things one after the other in time.

I do not deny to speech in general the power of portraying a bodily whole by its parts. . . but I do deny it to speech as the medium of poetry, because such verbal delineations of bodies fail of the illusion on which poetry particularly depends, and this illusion, I contend, must fail them for the reason that the co-existence of the physical object comes into collision with the consecutiveness of speech, and the former being resolved into the latter, the dismemberment of the whole into its parts is certainly made easier, but the final reunion of those parts into a whole is made uncommonly difficult and not seldom impossible.Lessing's critique of ekphrasis is focused around Vergil's description of the demise of Laocoon in the Aeneid, which Lessing compares negatively to the Laocoon statuary, pictured above. He quotes the Mantuan: 'Bis medium amplexi, bis collo squamea circum / Terga dati, superant capite et cervicibus altis' (2.218-219), and claims that the imagination is able to see 'now only the serpents and now only Laocoön', rather than the whole picture together. When we return to Brueghel and his poetasters, we find the same problem: here we are able to see, in all its jewelled beauty, the painting which those labourers suffer so miserably to describe. All four poets enumerate one thing after the other, and yet are unable, by the very nature of their medium, to present the enchanting whole all at once—what I called its 'perfect ordonnance'. Each poem distends the image through time, abandoning the intricate relation of parts which gave the original its beauty. And so it must be.

*

150 years after Laocoon, Irving Babbitt, conservative 'humanist' and enemy of Mencken and Hemingway, published The New Laokoon (1910). The book begins as a calm, measured analysis of Lessing's work, and of artistic confusion in the Renaissance and neoclassic (or 'pseudo-classic') periods; by its finale it has descended, inexorably, into a titanic rant against the decadence of modern times. Its polemic shows through at every turn—Babbitt's good American Protestantism: the Italian aestheticians who seek to impose Aristotelian formalism on poetry are compared to the Jesuits, who 'in order to strengthen and centralize the principle of authority, were ready to multiply their minute rulings on moral "cases" even at the risk of suppressing spontaneity in the religious life'. (Pascal has left his mark!) And Babbitt's good American masculinity: he lambasts Romantic criticism as 'intended primarily for women and men in their unmasculine moods'. And so on.

(A digression on the joy of marginalia—I discover a combative pencil on the pages of my library's copy. Babbitt writes 'If all the arts are thus restless and impressionistic, the reason is not far to seek: it is because the people who practice these arts and for whom they are practiced are themselves living in an impressionistic flutter', alongside which a young Derridean has scribbled: 'Oho! Then the medicine fits the patient? Well, what's the odds? Why pray for a change of diet?'—the same wag, demonstrating a most noble contempt, later annotates a passage on man's inferiority to Nature, almost mediaeval in its snivelling humility, with the snarl, 'Wholesome yet detestable modesty'.)

Babbitt, like Lessing, is against 'word-painting'—but he attributes this vice more to the naturalism of the Romantics than to the neoclassical fallacy of ut pictura poesis. The Romantics, or 'Rousseauists' as he scornfully designates them, were so empty of serious ideas that they scrabbled to describe every insignificant thing they could get their hands on, aiming not for ideas but merely for suggestiveness:

Alfred de Musset insinuates that all this minute lingering over the senses of childhood was a convenient way of producing the maximum amount of "copy" with the minimum expense of intellect.Babbitt is right to note the great rise of word-painting or ekphrastic poetry after Lessing. I think his condemnation of poetic suggestiveness is also on the mark. As I have remarked more than once, so much poetry is content merely to describe. And this is the other problem of the ekphrases: not only do they lose the spatial harmony of Brueghel's painting, but they are relentlessly superficial, in a way that painting can afford to be, but literature not. Lessing and the Romantics collapsed poetry onto music, but words are not purely musical, purely temporal—they have meaning, semantic content—and this is what makes literature so much richer and more important than the other art-forms. Exegesis is the way we respond intellectually to art, and it is fundamentally verbal: analysis of painting and music can only be a pale reflection of the analysis of words, of texts. This is what is meant by a coherently linguistic world-view. To find our poets abandoning the interpretive richness of language, and treating words like colours, completely superficial, and content only to describe without creating—that is the banality of decadent impressionism, and it is a Romantic excrescence.

*

A postscript on Lessing's legacy. Writers in the 20th century wrestled with the problem of overcoming the temporal nature of texts. Joseph Frank ('Spatial Form in Modern Literature', 1945) famously cited Ulysses as an archetype of spatial literature, arguing that the novel is not read but only re-read, creating not a linear temporal sequence in the mind but rather a 'system' or arrangement of objects in space, transcending time—Dublin, Thursday June 16, 1904. What is ultimately important is not the music of the words read aloud, but the picture built up by the intellective process. One might read Proust the same way, with its temporal worm-holes generated by Marcel's memorative activities, cutting against the flow of time. Or, indeed, Wordsworth's Prelude, especially in its 1850 form, where the shallow Romanticism of the original has indurated and become cold with the passage of many years.

Like Frank, Northrop Frye (The Critical Path, 1970) emphasises the internal over the external aspects of art: how the reader reads, the viewer gazes, and so forth. He demonstrates how linearly we can 'read' paintings—and Hunters in the Snow is a good example, with its diagonals that force the eye—and how spatially we can read music, as notes on staves. In the more famous Anatomy of Literature (1957), Frye essays the interpretation of poems as structural (spatial) wholes, just as Aaron Haspel did a few days ago with Ben Jonson's 'To Heaven'.

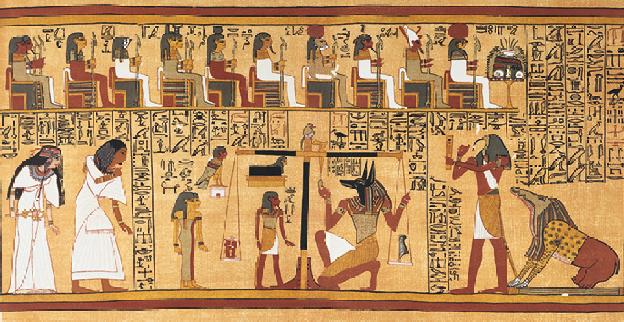

To continue in this vein, we speak of memory. Frank refers to a process of constructing a picture in the mind, which is a function of the memory; and to this we relate the work done by Yates and Carruthers on the ars memoria, the classical mnemotechnic mapping of a speech (ideas in succession) onto the rooms of a palace, or later the cells of a grid, in a spatial layout. At the climax of Yates' book is the work of Giordano Bruno, whose mystical Latin treatises promise more than mnemonic devices, becoming instead meditative manuals for the absorption of the entire world into the confines of a man's mind, the spatial microcosm. Compare this, finally, to a passage I once wrote about the Egyptian Book of the Dead (above), supposedly memorised by the believer before death so as to overcome obstacles in the afterlife:

The dead man prays to the 21 columns of the mansion of Osiris, to the four rudders of heaven, to the 42 chambers of judgement, and to the parts of his own body—which we are to identify with the parts of divine bodies, and with the parts of the underworld itself, taken as a configuration in space of architectural elements.

The text as a whole, when memorised, possesses almost no temporal qualities whatsoever; it constitutes itself a metaphorical space, huge and obscure, timeless, exactly like the space of the underworld which it describes. And perhaps to the early Egyptians, the memorisation of this text, with its attendant structuring of the mind, provided some comfort from the terrifying vision of their impending death. In acquiring themselves, like the text, spatial rather than temporal mentalities, they may have attained a sense of immortality even before trial.

18 comments:

Nice post. But Lessing isn't "marking a watershed between the neoclassic and romantic eras of German taste" - he and his essay are well in advance of Weimar Classicism and certainly not on the cusp of German Romanticism. He might be categorised as a writer of the German Enlightment, an Aufklärer.

Thanks!

True, but it's a knotty problem, because the main proponents of 'Weimar classicism', Goethe and Schiller, seem to have a decidedly Romantic flavour: Terry Pinkard talks about the "incendiary jolt" occasioned by Wether, with its 'cult of feeling', while Schiller is best remembered for his "Ode to Joy", set to music by a certain Romantic composer, and for his "Aesthetic Letters", which talk about art as the spontaneous eruption of energy from an artist.

The work of Rousseau on languages (early 1760s), a quintessential Romantic document, would sow its seed in Germany with Herder's treatise on the origin of language in 1772.

The classicism of Germany in the early 18th century is perhaps largely foreign in origin, though compare the philosophical impact of writers like Wolff and Thomasius, who conceive the enlightenment in classical terms, of the State providing order to society. Lessing's book engages with the neoclassical fallacy of 'ut pictura poesis', and takes time out to review the great neoclassical monument that is Winckelmann's book on Greek art (1764).

How can I not comment on a post that begins with the picture of a

statue ?

Regarding the poetry that tells stories -- I've memorized some

-- but definately don't feel like I have simultaneous access

to all the lines. It downloads from my memory -- and is

re-experienced one line at a time.

Regarding sculpture (and painting) -- I might be kind of

obsessed with its simultaneity -- that is -- I feel that it

hits the mind ---- zap --- and everything that follows is an

afterglow -- until I can muster enough energy -- and distance --

to take another hit. It's quality is not a topic

for careful deliberation -- except as required for conversation.

So now I'm thinking now that an analogy to baseball might be appropriate:

the batter sees the pitch that's traveling at almost the speed

of thought -- he makes an instant response -- and if it's the

right response -- whammo ! -- there it goes ! -- set

off the fireworks. (except, of course, that this pitcher wants to

share in the batter's success- Which is also why I don't

think that art appreciation offers an opportunity to show

how smart/clever/well-educated one is))

Indeed... thanks for your comment. There seems to be something about baseball that makes it appealing for people to use as intellectual analogies. Yes, it is the quintessential American sport--but why never basketball or American football?

Also, wouldn't sculpture, as opposed to painting, take more than one glance to take in, being three-dimensional?

I began to sketch a reply to your last post on ekphrasis several weeks ago -- it is still in the works. And now you have come up with the next one already! Slow down, will you?!

Unlike stanzas of poetry -- I don't think that the views of a sculpture have anything to do with each other -- and they are ususally of different qualities - with, hopefully, at least one that is memorable, with the rest being acceptable.

This led at least one sculptor/philosopher (Hildebrand) to suggest that sculpture relief is preferable to sculpture-in-the-round.

"This led at least one sculptor/philosopher (Hildebrand) to suggest that sculpture relief is preferable to sculpture-in-the-round."

I can't make much sense of this, I have to admit. Why unnecessarily limit the communicative/expressive richness of the medium? It sounds like a suggestion that literature should minimise semantic ambiguity, or painting should be in black and white.

I would have thought a priori that the most interesting aspect of sculpture was its tension between being a unified object, and the different appearances of its various angles.

I had an interesting exchange with Crhis about it. He suggested that the way to get into sculpture was to line draw it because it lets you get away from the narrative nonsense and get into the swaying of the lines. That really struck a chord with me: a sensation of swaying is what I get from looking at a lot of sculpture which I like. (Perhaps all). Calligraphy is like that for me, too: my mind traces the lines in a kind of dancing movement. It's almost as if the lines of the script were a record of the artist's movements -- like the grooves on the phonograph record are a record of the music -- they are a medium with the help of which to reproduce the actual work. I don't post much about painting because, by and large, I cannot find the words with which to describe what it does to me.

Note that calligraphy is a "consecutive" art. Still, there is very little one can *say* about the experience of appreciating it.

It seems that calligraphy would be somewhere between consecutive and simultaneous: somewhere between a text and a painting.

"I would have thought a priori that the most interesting aspect of sculpture was its tension between being a unified object, and the different appearances of its various angles."

The problem is that this tension is just a consequence of the sculptor's priorities (Front view most important -- top view unimportant -- etc) It's something the sculptor is stuck with -- rather something that's been planned for.

So I'm thinking it's a mistake to consider a sculpture as a unified object (unless you have the job of carrying it !)

Think of all the possible views -- high - low -- close -- far -- stong light -- dim light -- front -- back etc. Do you really want to consider all of these ?

How many times, for example, is a famous sculpture (like the Laocoon) presented by a photograph of the side view ? Usually, museums are content to present one view -- and usually, when I'm in a musuem, I walk around a piece until I find the view that gives me the biggest kick.

This is a way in which sculpture-in-the-round (and architecture) really is different from literature, painting, and music -- with the artist making multiple possible presentations -- some of which are sacrificed to others.

The problem doesn't seem to be so bad in a small piece -- but super-monumental size free standing sculptures are almost impossible not to present multiple terrible views.

(example: statue of liberty)

"Think of all the possible views -- high - low -- close -- far -- stong light -- dim light -- front -- back etc. Do you really want to consider all of these?"

In theory, why not? When you are limited to a more-or-less figurative rendition of the human form, this might be more difficult: but even so, I don't see why you couldn't create figural groups, even ones which presented interesting top-views, eg. heads looking up, or like a symmetrical Renaissance fountain with figural sculpture.

In fact, figure-groups are the most interesting, probably, as they can recreate a drama from every angle, even the backs of figures.

And when you come to architecture--which I strongly dissociate from sculpture, incidentally--all views are exceedingly important: the great buildings look good wherever you stand, inside or out: in fact, great buildings, or building-complexes (my favourite example being the London Barbican) enclose the viewer and force him to interact spatially with the environment, 'creating' his own views or sequence of views.

It seems that calligraphy would be somewhere between consecutive and simultaneous: somewhere between a text and a painting.

There are of course those comic-strip-like paintings -- like the B-whatever chapel in Florence (Masaccio's opus major), with St Peter now here now there, performing different "acts" in the various planes of the same picture; Gozzoli's St Francis cycle is like that, too.

Brancacci chapel.

In fact most fresco cycles can be read that way -- Gozzoli's Procession of the Magi in Medici-Ricardi, for example. I am not a big fan of the theory of the "frozen moment". (Er...Shaftsbury?)

"There are of course those comic-strip-like paintings"

Yes, I was thinking of mentioning those, but I don't really have sufficient knowledge of the genre. They do present an interesting counter to Lessing, like calligraphy.

"I am not a big fan of the theory of the "frozen moment"."

Do you mean of paintings which are frozen moments, or the frozen moment theory of painting? If the latter, I would say that it is certainly an interesting / valuable insight, but it does not tell the whole story, and there are many subtleties. Perhaps the topic for a future post.

:Do you mean of paintings which are frozen moments, or the frozen moment theory of painting?:

Duh, I'm too hangovered to notice the difference. I stayed up till 2 listening to Shostak's Lady Macbeth. It's amazing and available online for free for a few days, see my blog. Don't miss it. It's INCREDIBLE.omlwu

PS Now that I have sobered up, it occurs to me that the issue is confused by a theoretical error. I detect an assumption that some art is/is to be perceived this way (consecutively) and other that way (instantly). But we know from experimental work, including live brain CAT scans that art/music objects can be processed in a number of *alternate* areas of the brain, by, as it were, different brain modules; alternate is the key word here: sometimes they appear to be functioning simulataneously, but oftentimes -- usually -- they take turns -- mutually excluding each other. And so a person asked technical questions about the music he is hearing may be able to make very precise verbal reports but not able to report its emotional content, or vice versa.

(Professinal training can alter that -- we literally learn to use our brains better. And so, it takes a trained musician to hear the lyrics AND simultaneously count the high Cs). In this lies the secret of the strange phenomenon that one can have very different reactions to the same work on different occasions.

As a footnote I'd like to add something my father once said to me upon discovering the Szymanowski violin concertos: "one has to listen to them in way completely different from the way in which one listens to Romantic music". I think that may well be a case of learning to apply a heretofore underused brain module to a situation in which it has never been used before (by the particular individual).

ta-ta

back to my lady mcbeth

Post a Comment