Illius me paenitet dux

It was soon decided that tonight's dinner should be roast duck, preferably bloody. We had it and all, with shredded cucumbers and delicious hoisin sauce.

Labels: London

George: You want me to roar?

Mossop: Well, of course we wish you to roar. All the great orators roar before commencing with their speeches. It is the way of things. Ah, Mr. Keanrick, from your Hamlet, please.

Keanrick: Hh-hm. (orates) OOOOoooohhhhh. . . To be or not to be.

Mossop: From your Julius Caesar.

Keanrick: OoooHHHHOOOOHHH. . . Friends, Romans, countrymen.

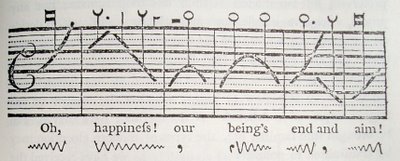

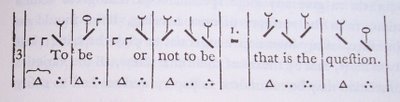

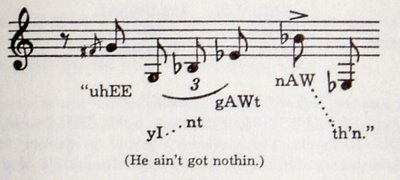

By what logic it can be contended that a system which leads to such “monstrosities” (the word is that of an admirer of Steele) as this is “masterly,” some readers, at any rate, will find it difficult to imagine. Either Steele’s scansions are justified by his principles or they are not. If they are, these principles are self-condemned; if they are not, the perpetrator of the scansions must have been a man of so loose a way of thinking that he cannot be taken into serious consideration. In either case, he cannot have had an ear; and a prosodist without an ear may surely be asked to “stand down.”Míâòw! Rasula/McCaffrey and Hatfield are more complimentary, the former labelling the Prosodia Rationalis as 'the most ambitious attempt of its time', the latter concluding that 'Steele’s descriptions of intonation and notations are essentially accurate and functional', although ultimately 'a musical notation inherently suggests a certain structure to the tonal space of speech, which just does not seem to be present'. For Richard Bradford ('The Visual Poem in the Eighteenth Century', Visible Language 23.1), Steele points towards a very Modernist aesthetic of language as pure sound:

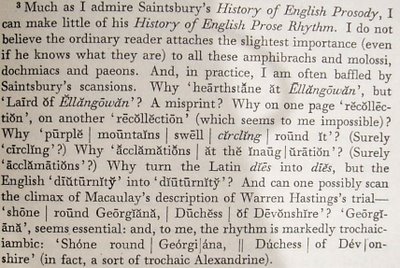

Steele’s concept of musical form in language has been drawn out beyond its status as an analogy, to the extent that the substance, the material, of language can present us with a sphere of appreciation quite separate from its meaning—wordless music.Despite its neglect, Steele's example stuck, and his book is the first (and almost the most complex) of many descriptions of speech in terms of tones and music. George Saintsbury obsessively scanned classical English prose by arcane metrical feet in his 1912 History of English Prose Rhythm; Joyce used it in the composition of the 'Oxen of the Sun' chapter from Ulysses. I don't have a copy of that book to hand, but this mini-critique, a footnote in F. L. Lucas' 1955 Style, should give the reader some idea of the original:

Labels: Early Modern, language

Labels: Conrad, philosophy

Labels: commonplace, Early Modern, history of science

Minimalism, maximalism, shorts, ruffles, braces, cropped jackets — the trends for this spring are a nightmare. Not only are there more of them than ever, they all contradict each other. Just what, exactly, are we supposed to wear? The answer this time around is: whatever you want. Never has fashion been more about personal style, about what appeals to you.— Tiffanie Darke, Sunday Times Style section, March 19, 2006.

Labels: commonplace

The halo sometimes seen round the moon is called the 'bor' or the 'burr', and when it is near the moon the rain is far—'Near bur. Far rain.'Carl Van Vechten's The Tiger in the House (1922), online here, explicitly compares Darwin's line about cats to passages from John Swan and Robert Herrick. As Vechten remarks, 'Cats in many quarters of the globe are held responsible for the weather; they are actually said to make it good or bad.' Darwin's verse is a composite of these sayings and epigrams. But being a composite, it loses the quality which defines the epigram: brevity, symmetry and balance. It is written in an iambic tetrameter, which lends itself to short lines with a heavy caesura, just like an epigrammatic couplet, such as this one by Goldsmith:

When oxen low and midges bite

We all do know ‘twill rain to-night.

When dogs eat grass there will be rain.

When cattle lie much rain is expected.

When the smoke rises straight up from the chimney, it will be fine, but when smoke donks it will rain.

A coming storm your shooting corns presage

And aches will throb, your hollow tooth will rage.

For he who fights / and runs awayThe first line balances the second in sense, rhythm and rhyme, and the first and second halves (hemistichs) of each line also balance each other across the caesura: this gives the epigram its characteristic solidity, a self-completing whole. (In this case, as it happens, another couplet provides an additional layer of symmetry.) But in a longer verse like Darwin's, the metre flags and plods as a series of disjointed couplets, each balanced internally, but none overtly relating to the other:

May live to fight / another day.

The sky is green, / the air is still,There is a fluency neither of rhythm, nor of meaning—it is a paratactic, as opposed to a hypotactic style. Only twice (lines 12 and 42) is a couplet continuous in sense with the next, and each time divided by a strong pause. The images have no temporal relation with one another, except for an occasional reference to 'last night'. In fact, there seems no definite time-frame at all, as 'the sun doth rise' follows 'a rainbow spans the sky', as if the latter were at night; again, Betty's corns 'torment' her in the present tense, but 'sent' her to bed in the past tense, if only for the sake of a rhyme. It is a deadened style, evoking not the life of nature, but rather a series of views, without context, unable to progress or develop. What we are offered, in effect, is the same thing presented over and over again, using different metaphoric images, like a man struggling in vain to communicate.

The mellow blackbird's / noise is shrill.

The dog, / so alter'd is his taste,

Quits mutton-bones, / on grass to feast.

And this also is a sore evil, that in all points as he came, so shall he go: and what profit hath he that hath laboured for the wind?In fact, the behaviour of wind in this poem is pretty strange. Contrast:

1 / The hollow winds begin to blowto:

25 / The wind unsteady veers around

33 / The whirling wind the dust obeys

37 / The sky is green, the air is stillLine 37 seems contradictory, but it comes at the turn of the poem, well hidden, occupying lines 35-40. In this passage, everything is topsy-turvy: the frog changes colour, the sky is green (ever seen a green sky?), the air is suddenly still, the blackbird is mellow but his song shrill, and oddest of all, the dog stops chewing on his bones and begins eating grass—unnatural, and likely to lead to the mutt's malnourished demise. After the turn are two images in succession of animals feigning death. 'Signs of Foul Weather', then, describes the superstition and foreknowledge of approaching death; but not the fear of death. The rainbow and the rising red sun (triumphant over the night) are ancient symbols of regeneration and promise. The last note, however, is melancholic, with impending rain—the tears of the bereaved—and a solemn realisation that there will be 'no working in the fields to-morrow': nobody, that is, to work.

Labels: literature

Apologies to my readers; Conrad has been on holiday in Bruges, Flanders, with his beloved wife. Not much to tell: it's a dull town for the most part. I enjoyed the excellent beer—the bruin house-draught at Cambrinus being my favourite—the linguistic oddity of Dutch (being the only European language not to call an orange an orange? No, apparently the Scandinavians also call it a Chinese apple), the odd art-installations and confession-box turned computer-station at one random church in the back streets, and the iconographic continuity of the chaliced serpent and standard-bearing lamb—Johns Evangelist and Baptist respectively—found throughout the paintings of the mediaeval Oud Sint-Jan Hospital, and constituting the logo of the new Sint-Jan Hospital.

Normal posting resumes tomorrow.

Labels: adventures

bedecktsamiger StapelThe thread and narrative of the sequence is in fact a series of motifs, from birds to various roundels to falling timbers to skeletons and popes. The more famous La Semaine, of which a Dover reprint is easily available, is divided into days corresponding to physical elements and visual motifs; its structure is simpler and less intuitive than La Femme, which in turn is more surprising and inventive. They correspond, in their own way, to the two automatic texts produced by Brèton and Soupault, Les Champs Magnétiques and La Conception Immaculée, the first being freeform and anarchic, the second segmented and systematised. I prefer the former in each case.

mensch nacktsamiger wasserformer

("edelformer") Kleidsame nervatur

auch

!umpressnerven!

Labels: art, literature

He pretends to be clumsy and knocks the chess pieces over with the hem of his coat. He looks up at DEATH.On October 16, 1987, in the small hours of the morning, a young Conrad Roth, barely turned six, was woken up with a start when his large world-map came off his bedroom wall with a crash. His world was, quite metaphorically, coming down. The panes were rattling and outside the trees were heaving ferociously. It turned out to be the Great Storm, the worst winds in British history. I don't have many memories of that time. But Hampstead Heath remembers: the Heath is like the mind for Freud, that never forgets, leaving always the sigils and markers of trauma, or the Dianetic engram, 'a mental image picture which is a recording of a time of physical pain and unconsciousness. It must by definition have impact or injury as part of its content'.

KNIGHT: I've forgotten how the pieces stood.

DEATH (laughs contentedly): But I have not forgotten. You can't get away that easily.

DEATH leans over the board and rearranges the pieces.

Labels: London

To what is this a beginning? Not hard. To the selection that was selected in Gaelic since this is the beginning which was invented by Fenius after the coming of the school with languages from abroad, every obscure sound that existed in every speech and in every language was put into Gaelic so that for this reason it is more comprehensive than any language.

Query, what are the definite numbers of Nimrod's Tower? Not hard. Eight of them, to wit, 72 counsellors, 72 pupils, 72 races of men, 72 languages, the languages in his school, 72 peoples whose were those languages, and the races, 72 artificers to work at it, 72 building materials including lime, bitumen, earth, and cement in equal layers, 72 paces in width. . .Languages become part of the edifice, like bricks in a whole. This is why the Auraicept goes onto say that according to different accounts, 'only nine materials were in the Tower, to wit, clay and water, wool and blood, wood and lime, acacias, flax thread, and bitumen', which correspond to 'noun, pronoun, verb, adverb, participle, conjunction, preposition and interjection'. Which is only eight. Oops. I imagine clay and water to be the noun and the verb, solid and liquid, the two primary components; blood for the personal pronoun, flax thread for the conjunction and fiery bitumen the interjection. I don't know about the others. You'll notice that 'participle' is listed as one of the parts of speech; this follows the classical notion (see Varro 6.36) that words can be divided binomially according to whether they possess time (verbs), case (nouns, adjectives), both (participles) or neither (everything else—commonly divided into adverb, conjunction or preposition, and sometimes interjection).

the letter [litera, expanded to legitera] is as a road for reading [legendi iter] inasmuch as it prepares a way for the reading:Then a Gaelic equivalent is attempted, the word for 'letter' being gutta:

voice foundation [guth fotha], ie. foundation of the voice is that: or voice sent [guth fuiti], in respect that voices are sent through them: or voice ways [guth seta], in respect that they are ways of voices. . . or a voice place [guth aite], ie., they make a voice in place: or they vocalise [guthetait], ie. in respect that voice comes through them alone.The process of etymologising here is not to find the true root (etymon) of the word, but as a sort of magic with words, a temurah, the notion being that all products of the same sounds are ultimately equivalent. And language is wood, too, for the Ogham is the Bethe Luis Nin, the tree alphabet, letters carved into bark. As Cassiodorus delights in reminding his reader, liber (book) is from liber, free, as the bark (liber) from the tree. And 'Fidh, wood, is from the word funo [φωνέω], I sound, or from the word fundamentum, ie. foundation. . . Now, as to fid, wood, good law is as its meaning, both artificial and natural'. Taebomnai or consonants are the sides of oaks, 'from the fact that material for the words is cut out of them'. Wood was the stuff of the universe for the Greeks, first xyle then hyle. I always wondered about that fact. The connection was made for me also by George Guess, who concocted a syllabary for the Cherokees in the 1810s, and who gave his native name to the Sequoyah tree. I wrote a poem about it once.

This general shaman tells heavens to the earth,The Irish literature of the early mediaeval period is a goldmine, full of strange linguistic adventures, such as the Hisperica Famina poems, written in bizarre macaronic Latin. The Auraicept is a product of that sensibility, overflowing with ideas, words, stories, a light in the dark, grammatic fantasy, a memory of religion and language made into new systems, and a fertile tributary in the river watering the immense gardens of Finnegans Wake.

his red wood pricking the elements;

in his girth, in his height, in his signed barks,

in the light that sparks on his moss-lined trunk,

in his xylems and fluid phloetry, in ants patterning him,

in the galed twittering of branches,

most of all in pulp, paper—read wood—

this tree whispers encoded heavens to the earth.

Labels: language, literature

Lo! the Bat with leathern wing,

Winking and blinking,

Winking and blinking,

Winking and blinking,

Like Dr Johnson.

Aldiborontiphoscophornio!

Where left you Chrononhotonthologos?

Let the singing Singers

With vocal Voices, most vociferous,

In sweet Vociferation, out Vociferize

E'vn Sound itself.

. . . all the magic Motion

Of Scene Deceptiovisive and Sublime.

King. What ails the Queen?

Aldi. A sudden Diarrhaea's rapid Force,

So stimulates the Peristaltic Motion,

That she by far out-does her late Out-doing

And all conclude her Royal Life in Danger.

Day's Curtain's drawn, the Morn begins to rise,

And waking Nature rubs her sleepy Eyes:

The pretty little fleecy bleating Flocks,

In Baa's harmonious warble thro' the Rocks

Say she has got the Thorough-go-Nimble.

Whole Magazines of galli-potted Nostrums

Pity that you, who've served so long, so well,

Shou'd die a Virgin, and lead Apes in Hell.

He sleeps supine amidst the Din of War:

And yet 'tis not definitively Sleep;

Rather a kind of Doze, a waking Slumber,

That sheds a Stupefaction o'er his Senses;

For now he nods and snores; anon he starts;

Then nods and snores again: If this be Sleep,

Tell me, ye Gods! what mortal Man's awake!

¿Qué es la vida? Una ilusión,

una sombra, una ficción,

y el mayor bien es pequeño:

que toda la vida es sueño,

y los sueños, sueños son.

— Pedro Calderón de la Barca, La Vida es Sueňo

Henceforth let no Man sleep, on Pain of Death:

Instead of Sleep, let pompous Pageantry

Keep all Mankind eternally awake.

Labels: Early Modern, literature

Labels: miscellaneous

This does not—repeat not—mean that the Lit. Supp. will not on occasion censure a book, or even damn it, with all the critical fervour and talent at its command (which is considerable); but of this much you can be certain—it was well worth damning.Meanwhile, Barclays Bank quotes Browning and uses language like 'the colour of dangers and alarums' and 'We cannot, alas, scatter these facilities with a fine, careless rapture'. How quaint! As for the articles, they just pile up, one after the other, about the bleak loneliness of modern life, some scientific, others emotional, with some charmingly trite poetry too ('I do not want to be consoled / because this grief is all I hold'), literary quotations, and cartoons without punchlines. The most interesting thing in the book is a piece by the Chicago journalist and scriptwriter Clancy Sigal about alienation among intellectuals.

Labels: philosophy