On vit tranquille aussi dans les cachots;

en est-ce assez pour s'y trouver bien?

Two hours last week in

Kensal Green Cemetery, NW London—the intangible suspicion of a very religious experience indeed. I armoured myself with a long-sleeved floral shirt, even in the terrific heat, and despite the stares of daylabourers, so as to protect myself from the offered arms of this place. But my unconscious would have none of it, and so I let my feet go in nothing but a pair of terracotta sandals, and walked with my toes among the dead. The green was rife with the odour of fresh-cut grass, and as I explored, foolishly frixonaseless, my nares burned and formicated with allergies. At key moments, the sun broke his cover to illuminate the stones and the quiet blizzards of gossamer, everywhere. Even the waxy block in my right ear unstopped itself for the occasion. The cemetery crowded into me on all sides, as I would have it, or not.

A quiet surrealism

I've been discussing this project with Richard of

Castrovalva, whom I've never met, but whose no-nonsense blog I very much enjoy, despite the disappointing infrequency of his updates. He's taken the guided tour, and

posted his own observations, with historical notes, and some handsome pictures of the cemetery. He offers this helpful introduction:

As the population of nineteenth-century London increased and social conditions deteriorated, the demands on London's cemeteries rapidly exceeded the available space. High property prices and the crowded condition of London’s churchyards led to incidents of bodysnatching and of older graves being emptied to make way for the new. The solution, for the upper and middle classes at least, was to build seven new cemeteries at a remove from the city, of which Kensal Green was the first. Funerals promptly went into fashion and came to cost far more than weddings, with both the ceremony and the tomb having to be as grandiose as possible.

It was only in 1968 that cremations became more popular than burials at the Green, and now a sizeable proportion is given over to the Crematorium and its surroundings. The great majority, however, remains all tombs and bones.

Who builds stronger than a mason, a shipwright, or a carpenter? When one enters a cemetery, one becomes suddenly attuned to the power of words and images; all things acquire a new resonance. The first name that came to mind was, naturally,

Harrow Road, which suggests the tilling of the gravesoil, and the

Harrowing of Hell. Once inside the gates, I think not of

cemetery, the 'sleeping-chamber' (

F—— J——— fell asleep on June 19, 1926), with its overtone of

symmetry—but of

necropolis, which in my mind is not just the city of the dead but the

polis of the dead, the city-state. For this place has not only its own avenues, but moreover its own domain, its own customs and laws, almost as if gravity has been suspended. To my left is the

Dissenters' Chapel, which irrevocably calls to mind, at least in such a place as this,

disinterred. By the chapel there's a gate, and a sign that reads

DO NOT RELY ON

THIS GATE

TO LEAVE THE

CEMETERY

and of course the thought that occurs immediately is—

there is only one gate that leaves this cemetery, and it's a painful one. The phantasy sets to work at once. And then all the names of the buried. Last time I was here, at the tender age of 20, I wrote a long poem, and compiled a list of these names, a list which conjures nothing less than the entire world:

REIDAR SJØBLOM

CHARLES ANDREW NOSOTTI

DUSAN RADOMIR BRANKOVIC

ESTHER LOUISA GROVES

MILOSH SEKULICH

MESIC C. BOGLE

ZABETH ANGELO LEVERONI

MINISTER IRAIH MAY CROASDAILE

WOIZERO MEHRET HABTOM ABRAHAM

JUNAVAN DOLICITA LEWIS

HENRY HETHERINGTON

REINHOLDS ZAKIRNIS

NOAMI ELIZABETH DRYDEN

RAYLEIGH CRYSTAL FITZGERALD

JOHN COONEY

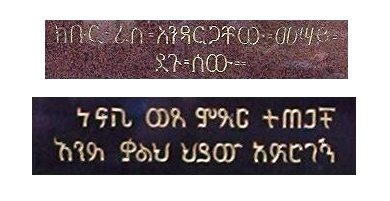

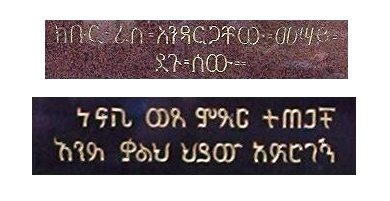

TSEHAFE T'IZAZ

CELIA MAY ALLEN

DWARKANAUTH TAGORE

PERCIVAL SAMUEL PORTEOUS

AGA MAUD ULLATHORNE ULLATHORNE

EDWARD OPPONG KYEKYEKU

JACOB OCEN TOYA

SYLVIA DUHANEY

LEVI SMALLING

There are printed leaflets, and even regular guided tours. But somehow it seems best to arrive ignorant, to allow fully the mystery, to be permitted a

why? And not to understand those strange alphabets, which I know or suspect really to be Ethiopic, but which I imagine nonetheless to be a coded outline of ancient magics. And occasionally the discomfortable

flash of recognition.

The cemetery is

dead entirely, not just under the earth. By the car-park I watch a fourbyfourful of blonde proles in faux-Chanel, there for a lunchtime's flowersetting, dead as could be. The gardeners seem to have been there for eternity, merrily pottering away, friendly for a

good morning—though eyeing my shirt mistrustfully, as if with

what a pansy! in mind, or envisioning in it another plot for their shovels—and quite content with life, having set aside a comfortable space for themselves among the lawns. Desperate for a drink, I am directed to the general taps in the gents' room, where I imagine the water running over the carcasses of Victorian aristocrats, and quite suddenly I taste, by the sheer power of suggestion, a little iron here, a spot of mud there, and the flavour of cholera. The

gasometer a stone's throw from the wall is itself a skeletal relic of the past. Even the monarchs and myriad gay petals have no longer any vegetative capacity. It's all

dead. (Praise be to the modulations of our language, to have that word for the clipped goneness of life, and this word,

death, for the dry rasp of the impending grave, or the suspiration of a last gasp.)

Broken column as stem and stone

The stones themselves are more like molars in a great carious jaw, grey with age. There are fields and fields of them, most plain, or with a stock design (cross, draped urn, obelisk, guardian angel, broken column, etc.), some furnished with ornamental coffins, steeples, enclosures, or entire mausolea for the Italian famiglie in the Orthodox gardens. You can buy a plot here for 2 or 3 grand, according to one of the gardeners, and indeed, graves for Jamaicans and other West London cosmopolitans are springing up all the time, complete with bouquet-holders and little beds of ground glass. Richard notes the presence of modern Cyrillic, Hebrew and even Chinese among the new graves. As a whole, though, Kensal Green remains terrifically Victorian. Here lie Thomas Hood, I. K. Brunel, Thackeray and Babbage. (Resisting even the last century, the place offers mocking imitations of modernist heroes: I see an ancient Wyndham Lewis there, a

JOYCE / JAMES here.)

I accept Kensal Green as a nation's face averted, retaining upon it all the idiosyncrasies of what once surrounded it. The Victorian ghosts are evident in their mania for colonial accumulation—the frequent Egyptian motifs, the neo-Gothic stonework, the Greek portico around the chapel, these Indian telamons (pictured right)—and in their endless capacity for simple poetic sentiment, a reaction, perhaps, to the pressures of the sprawling cityscape and all its new machines. In their ideals, too,

what people would be remembered for—military success, Christian piety,

humanitarian efforts for the poor, and an almost Roman devotion to the family. Are these the qualities and achievements praised on today's tombstones?

Richard notes, furthermore, the Victorian obsession with death, citing the huge literature of the period, from Little Nell to

Jane Eyre and

Wuthering Heights ("and wondered how any one could ever imagine unquiet slumbers for the sleepers in that quiet earth"), the elegies of Tennyson and Arnold—we might add Browning, whose 'Epilogue' is quoted on

this grave—as well as Bram Stoker, and E. A. Poe, who famously found the death of a beautiful woman to be the most fit subject for poetry, and whose

House of Usher might have been the inspiration for this sign:

DANGER

DANGEROUS STONEWORK

& COLLAPSING GRAVES

Death does inspire the most beautiful of proses. Richard makes the almost obligatory Thomas Browne reference, much loved in the 19th century for his meditations on mortality in

Hydriotaphia and

Letter to a Friend. And Browne inspired the greatest of the Romantic essayists,

Charles Lamb, whose description of a faded, post-Bubble

South-Sea House might frame Kensal Green itself:

I dare say thou hast often admired its magnificent portals ever gaping wide, and disclosing to view a grave court, with cloister and pillars, with few or no traces of goers-in or comers-out—a desolation something like Balclutha’s.

Less monumental, but more typical, is the work of Marie Corelli, the Queen's own favourite; here's the ending of

The Mighty Atom:

Lionel’s grave was closed in, and a full-flowering stem of the white lilies of St. John lay upon it, like an angel’s sceptre. Another similar stem adorned the grave of Jessamine; and between the two little mounds of earth, beneath which two little innocent hearts were at rest for ever, a robin-redbreast sang its plaintive evening carol, while the sun flamed down into the west and the night fell.

Yes, the Victorians were fascinated by death, both as a medical phenomenon—Walter Whiter's 1819

Dissertation on the Disorder of Death ruminated on suspended animation and the possibility of resurrection, while numerous early science-fiction works would spin a plot out of the deferral of death—and as the locus for poetic sentiment. The latter goes back as far as the Graveyard Poets, and in particular Gray's seminal

Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard (1750):

Can storied urn or animated bust

Back to its mansion call the fleeting breath?

Can Honour's voice provoke the silent dust

Or Flattery soothe the dull cold ear of Death?

The same mood would continue as late as Thomson's terrific

City of Dreadful Night (1880), ballasted also with that dreaded wave of nihilist atheism surfacing in much Victorian thought and literature:

The open spaces yawn with gloom abysmal,

The sombre mansions loom immense and dismal.

Richard mentions the influence of the evangelical revival on this death-fixation, as well as the cult of tuberculosis and wasting-diseases, the draining of one's life-force. That life-force gripped them in the wake of Mesmer and

Reichenbach, eager to snatch up something away from the scientists, and keen also for transcendence in the dearth of earlier magics. Charles Kingsley's Tom is not killed but transformed, and Lewis Carroll could hardly bear the thought of death spoiling the play of

Sylvie and Bruno. It was sort of a

grand naivety. But I wonder if there is more to it than that. Why, by the end of the century, had the same morbidity crept into the decadent and symbolist literatures of the French? The Continentals, naturally, were so much darker and more brutal about the subject. Compare these paintings:

Millais, 1852

*

The graves and markers of children and infants catch my eye continually, almost always over-farced with toys and notes. I've heard it said that the Indians have a particular fear of the ghosts of children in their graveyards. The death of children was the great Victorian terror, infant mortality being

preposterously high in the filthy cities of the 19th century; these plots, however, are very modern. There is a wealth of imagination to these, grief occasioning a florid externalising of the spirit.

This last in fact is in tribute to a father, set off with a bunch of graves in an enclosure high to the north. I presume he was a fruiterer, though there is only the suggestion of narrative here.

*

Richard's experience was that 'Kensal’s ugly brick walls do little to insulate it from the world of the living', due to the looming presence of the gasometer and Trellick Tower. But I found it quite secluded, and only too easy to get lost. Like Richard, I am 'enough of a Romantic to be fascinated by decay and ruin', a taste that goes back to the Quattrocento, when guidebooks to the Roman ruins were published by starry-eyed Italian humanists. The cemetery is full of tombs untended and wild with growth:

And of tombs in various stages of dis int eg rat i o n, stones falling to pieces in the weight of the quiet. This the first stage: a poetic sight, Peace decapitated,

la femme sans tête, as if in some grim classical satire of the world:

And the second stage, the aphesis and extreme effacement of horse and seated owner, encrusted with mosses, and now wholly anonymous—the fall of the cavaliers. Nonetheless the great beast, I think, retains an uncanny power, dwarfing the faceless man by his front leg.

And finally the

multiplication of arcs—arcs as in arks,

arcae, even arcophagi—and the trituration of all former stones—not yet ashlar, but still the basis for a reconstruction of the entire cemetery.

It was a troubling afternoon, all told. Not for nothing, Richard reports, is it said 'that the Victorians treated death as simply another territory to be conquered'. Kensal Green resists comprehension, like the rest of the world; it is a territory which will not be conquered. There are questions I cannot even formulate, let alone answer. Broken narratives are strewn about the grounds in their thousands, microcosmically. It is an environment which speaks so much without words, and with words made fragmentary and gestural,

formulaic, and in letters foreign and cryptographical, as to challenge the roots of a coherently linguistic world view. I want to go back, and yet there is nothing left to see, except the catacombs, which I had no chance to explore. Richard has

reported on some of the lesser-known inhabitants of the cemetery in his own blog; I suggest you go read that, and

Chris Miller on Graceland Cemetery, and all the rest of it, and forget all about this state of rapt incommunicacy.

wrote a 20-page poem named Chalybea. The name, playing off so many related words, had so much resonance for me that a whole world seemed to spill out of it. It evokes the currents of a water deeper than all men, a spring or an ocean of thought, and the iron rising out of it, the iron in the blood, the iron of the steel of our new architectures, with water hardened into glass, and also the chalybeous blue of case-hardened steel, the blue of the deep, of piano notes, and of watch-springs, of the hidden mechanisms of time, stopped. I imagined a city with rivers of liquid glass, where a shortage of steel forces men to strip their clocks and watches for the springs, stilling the movement of time. The poem's protagonist, an admiral named Conrad, stages revolution from the sea against the city, but achieves nothing. Chalybea to me was an object of love, a face half effaced peering out from a wall, a goddess presiding over the iron and the waters of time, and of the unfinished act—'Her who has thy thirst subdued'.

wrote a 20-page poem named Chalybea. The name, playing off so many related words, had so much resonance for me that a whole world seemed to spill out of it. It evokes the currents of a water deeper than all men, a spring or an ocean of thought, and the iron rising out of it, the iron in the blood, the iron of the steel of our new architectures, with water hardened into glass, and also the chalybeous blue of case-hardened steel, the blue of the deep, of piano notes, and of watch-springs, of the hidden mechanisms of time, stopped. I imagined a city with rivers of liquid glass, where a shortage of steel forces men to strip their clocks and watches for the springs, stilling the movement of time. The poem's protagonist, an admiral named Conrad, stages revolution from the sea against the city, but achieves nothing. Chalybea to me was an object of love, a face half effaced peering out from a wall, a goddess presiding over the iron and the waters of time, and of the unfinished act—'Her who has thy thirst subdued'.

The cemetery is dead entirely, not just under the earth. By the car-park I watch a fourbyfourful of blonde proles in faux-Chanel, there for a lunchtime's flowersetting, dead as could be. The gardeners seem to have been there for eternity, merrily pottering away, friendly for a good morning—though eyeing my shirt mistrustfully, as if with what a pansy! in mind, or envisioning in it another plot for their shovels—and quite content with life, having set aside a comfortable space for themselves among the lawns. Desperate for a drink, I am directed to the general taps in the gents' room, where I imagine the water running over the carcasses of Victorian aristocrats, and quite suddenly I taste, by the sheer power of suggestion, a little iron here, a spot of mud there, and the flavour of cholera. The

The cemetery is dead entirely, not just under the earth. By the car-park I watch a fourbyfourful of blonde proles in faux-Chanel, there for a lunchtime's flowersetting, dead as could be. The gardeners seem to have been there for eternity, merrily pottering away, friendly for a good morning—though eyeing my shirt mistrustfully, as if with what a pansy! in mind, or envisioning in it another plot for their shovels—and quite content with life, having set aside a comfortable space for themselves among the lawns. Desperate for a drink, I am directed to the general taps in the gents' room, where I imagine the water running over the carcasses of Victorian aristocrats, and quite suddenly I taste, by the sheer power of suggestion, a little iron here, a spot of mud there, and the flavour of cholera. The

I accept Kensal Green as a nation's face averted, retaining upon it all the idiosyncrasies of what once surrounded it. The Victorian ghosts are evident in their mania for colonial accumulation—the frequent Egyptian motifs, the neo-Gothic stonework, the Greek portico around the chapel, these Indian telamons (pictured right)—and in their endless capacity for simple poetic sentiment, a reaction, perhaps, to the pressures of the sprawling cityscape and all its new machines. In their ideals, too, what people would be remembered for—military success, Christian piety,

I accept Kensal Green as a nation's face averted, retaining upon it all the idiosyncrasies of what once surrounded it. The Victorian ghosts are evident in their mania for colonial accumulation—the frequent Egyptian motifs, the neo-Gothic stonework, the Greek portico around the chapel, these Indian telamons (pictured right)—and in their endless capacity for simple poetic sentiment, a reaction, perhaps, to the pressures of the sprawling cityscape and all its new machines. In their ideals, too, what people would be remembered for—military success, Christian piety,