History of the Nod: Part II

Adam and his race are a dream of mortal mind, because Cain went to live in the Land of Nod, the land of dreams and illusions.Calvert Watkins associates the word nod with a number of 'loosely-related Germanic words referring to pinching, closing the eyes'—these include nap (sleep), nip (bite), nibble and niggard. It is, of course, unrelated to the Hebrew: and yet, I wonder if we can see in its use the ghost of Nod, of the wandering Jew? In English its earliest sense is, as a verb, to gesture with an inclination of the head; thus Chaucer has 'And on the manciple he gan nodde faste / For lakke of speche' (The Manciple's Tale, 47). 150 years later it comes to mean a quick inclination of the head. Around this time—except for a lone citation in Lydgate—the word is first used in print to refer to the process of dropping off to sleep. In the seventeenth century, this sense develops the shade of 'To be momentarily inattentive or inaccurate; to make a slip or mistake' (OED)—or, we might add, 'to wander'.

— Mary Baker Eddy, Science and Health (1875)

Specifically, the word is associated with a famous phrase in Horace (Ars Poetica, line 359), that even the greatest poets made occasional errors: bonus dormitat Homerus, now conventionally rendered 'even [good] Homer nods'. The exact phrase first appears, to my knowledge, in an anonymous 1782 book titled Strict Thoughts on Education: 'Even Homer nods, said Horace long ago'. Homer's nod had long been proverbial. After all, a nameless 1665 translator of Horace had written 'I hear good Homer snore'; but when Wiliam Hughes (Man of Sin, 1677) remarked, 'We see a Jesuite may sometimes nod as well as Homer', every translator wanted in:

Homer himself hath been observ'd to nodd. (Roscommon, 1680)Homer, we can see, has firmly colonised the Land of Nod: in 1733, with Vico's 'discovery' of the true Homer, he left Eden, and has continued to wander ever since, with a mark set upon him, lest any finding him should kill him.

But fret to find the mighty Homer dream,

Forget himself a-while, and lose his Theme:

Yet if the work be long, sleep may surprize,

And a short Nod creep o're the watchfull'st Eyes. (Creech, 1684)

When but a Trifle falls from Homer's Pen;

But where an Author swells into a Size,

Why should a Nod, or gentle Sleep surprize? (Ames, 1727)

Find I good Homer ever nodding yet. (anonymous, 1746)

To see ev'n Homer sometimes nod, or sleep. (Popple, 1753)

But fret whenever honest Homer nods. (Duncombe, 1757-59)

*

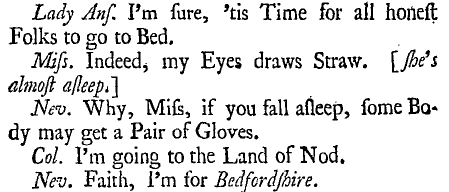

It was Swift who first formally introduced the word, nod, meaning drift off, back into the Biblical collocation 'Land of Nod'—which, with the belated triumph of the KJV, was by then a standard form. The use of the phrase to denote slumberland comes in a jocular passage from Swift's Compleat Collection of Genteel and Ingenious Conversation of 1738, bracketed by equivalent expressions:

It's a pretty good pun, when you think about it, and by the 19th century it was a common one. But the Land of Nod is not a place for settling: it is a condition of wandering and restlessness, the currents of the mind beneath a surface calm. By 1889 the phrase had acquired decidedly childish connotations, and in this year it would be transformed again, by the Denver journalist Eugene Field and his children's poem Dutch Lullaby. Field was a celebrated columnist, an eccentric and a prankster (he infamously lampooned Oscar Wilde). He was also a natural wanderer, and according to his brother Roswell, 'No matter where he wandered, he speedily became imbued with the spirit of his surroundings, and his quickly and accurately gathered impressions found vent in his pen'.

In his 1896 Auto-Analysis, a wry pamphlet forestalling biographical speculation after his death, Field wrote 'I do not love all children. I have tried to analyze my feelings towards children, and I think I discover that I love them in so far as I can make pets of them'. Such a statement, potentially alarming, captures the whimsy of a piece as charming and sentimental as the Lullaby. Here are the poem's first and last verses—

Wynken, Blynken, and Nod one night(It should have been 'close your eyes. . .', but still.) Like a good nursery rhyme, the poem runs in the sprung rhythm theoretised by G. M. Hopkins: the metric involves an alternation of four and three stressed beats to a line, with varying numbers of unstressed beats. It is a curious coincidence that in 1889, when this poem was written, Field was working on a series of Horace translations, including one into Chaucerian English—is it possible that he had in mind Homer's nod?

Sailed off in a wooden shoe,—

Sailed on a river of misty light

Into a sea of dew.

"Where are you going, and what do you wish?"

The old moon asked the three.

"We have come to fish for the herring-fish

That live in this beautiful sea;

Nets of silver and gold have we,"

Said Wynken,

Blynken,

And Nod.

Wynken and Blynken are two little eyes,

And Nod is a little head,

And the wooden shoe that sailed the skies

Is a wee one's trundle-bed;

So shut your eyes while Mother sings

Of wonderful sights that be,

And you shall see the beautiful things

As you rock on the misty sea

Where the old shoe rocked the fishermen three,—

Wynken,

Blynken,

And Nod.

The 'misty sea' of the Lullaby had appeared in another of Field's pieces, The Wanderer (1883), which his biographer Slason Thompson refers to as a 'little bit of fugitive verse'. This poem, like Dover Beach, recapitulates the crisis of faith in an image of the ocean—it refers to the long-standing controversy over seashells found on mountain-tops, taken by some as proof of the Flood, and by others as proof of tectonic activity. Field writes of such a shell:

Strange, was it not? Far from its native deep,The 'misty sea' is turbid and full of secrets: it is the sea of faith, apparently calm, but troubled always with the eddies and currents of doubt—a Land of Nod. Is this the misty sea recalled in the Lullaby?

One song it sang,—

Sang of the awful mysteries of the tide,

Sang of the misty sea, profound and wide,—

Ever with echoes of the ocean rang.

And you shall see the beautiful thingsCradles are rocked, and so is faith. The three heroes go off to fish for herring, an image recalling the apostles on the sea of Galilee (John 21:3); 'all night long' they cast their nets, but is it never said that any herring are caught. Perhaps Field himself has nodded in the detail; perhaps the Lullaby expresses doubts, too.

As you rock on the misty sea

*

Nonetheless, illustrators loved the piece, and it gave free rein to a gentle fantasy of the sea and moon:

Maxfield Parrish, 1905

Charles H. Sylvester, 1909

Parrish is a favourite with my wife; I find his colours garish and his composition flat, much preferring Sylvester's sinuous woodcut. In 1919, a sculptress by the name of Mabel Landrum Torrey made a statue-group of the three characters: first in marble for Washington Park, Denver, then two decades later a bronze copy for Wellsboro, PA, presented by the mayor of Denver, Fred Bailey, 'as a gesture of love for his late wife Elizabeth'. This webpage describes the scene:

It was a bright, sunny September afternoon in 1938 and 2,000 people gathered on the village green in Wellsboro, Pennsylvania. Bands played and children laughed as they anticipated the unveiling of a gift to the community. The cord was pulled, revealing a bronze statue of Wynken, Blynken and Nod sailing on its man-made sea and fountain.It would be just as well to recall Field's remark in the Auto-Analysis: 'I do not care particularly for sculpture or for paintings'.

5 comments:

In terms of establishing an etymology for the word, you might be interested to know that nd` in Ethiopic means to drive somebody out from before you and ndø means to be poor or destitute. It also turns up in the Amarna Letters as nadû (cast out, expel) and is assumed to be of West Semitic origin. It would have been nice if I'd been able to find a meaning related to 'sleep', but this seems to be a later Indo-European development.

There seems to be an obvious correlation between the Hebrew and Ethiopic, though... I wonder if any Nostratists have mentioned this connection.

No, I know, I meant about Hebrew and English. (I can see that my remark is misleading though.) I'll check this tomorrow.

I am an art historian reviewing a small version of Mable L. Torrey's sculpture. I am searching for information concerning the reproduction of this piece for National Public Libraries or Public Schools.

Please contact with information.

nearthistorian@msn.com

Janet

See also this photo of the sculpture:

http://npthompson.wordpress.com/2009/04/05/concealed-mysteries/

Post a Comment